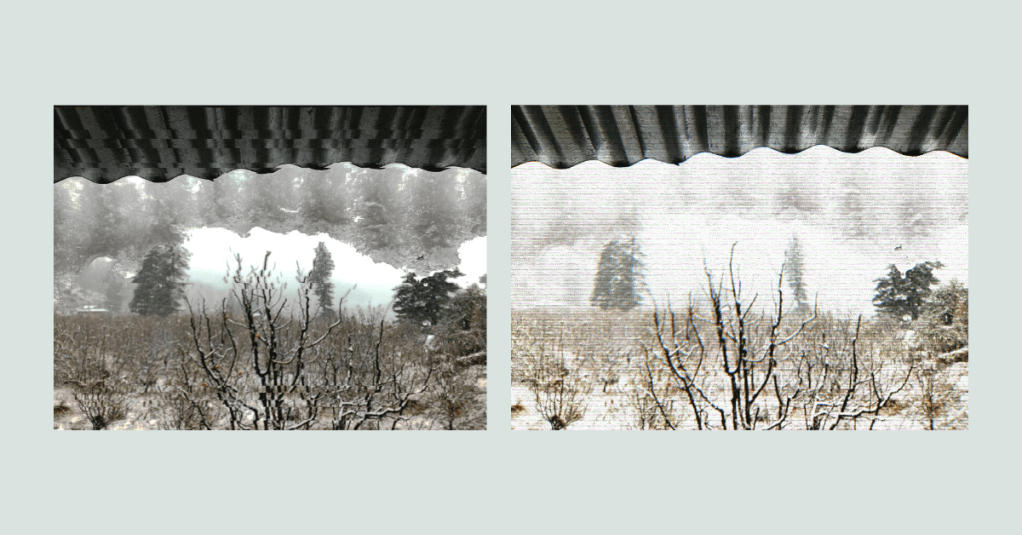

In Kalga, it was cold.

It was snowing; the Ground was cold, the Air was cold.

My friends were cold, I was cold. There wasn’t much to it.

There wasn’t much to it, to the cold in Kalga.

I called my friend and said, “It is cold.”

There wasn’t a reading to tell us of it.

Yet, he knew. “Yes, it is cold,” he said.

I wish there was more to say.

What was the nature of this cold?

It was snowing, and everything was cold.

That’s it, there wasn’t much to it.

What a failure of words, all this cold,

Only three words to put it.

“It is cold.” Then there was laughter.

Some context: I wrote this poem along with a paper on the nature of writing. I looked into the difference in writing as about the expression/becoming of the writer-self and writing as about the reflection/becoming of the reader-self.

Reading through Tagore, Kohak, and my own experiences, I noted that writing in the former frame becomes about recollection and is registered through an I, almost as a narrative of the writer-self. In the latter frame, the writing is registered at a more general level, the level of intuition, such that the I must not be evoked in recollection of it, the writing, instead, is retained by/in the reader.

In a very non-committal, almost evasive, fashion, yet with complete honesty, I concluded that all writing is almost always both – the reader and the writer are both eternally present and becoming in the text. The poem above was an attempt to intentionally write something which could be recollected and/or retained.